Special to Canadian Design and Construction Report

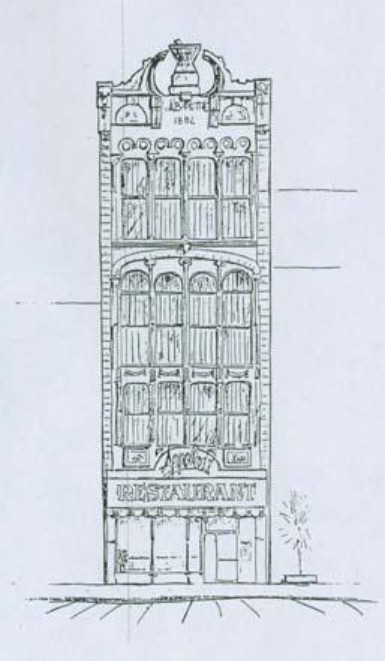

Among many purposes in the 1800s, cast-iron was used for gates and fences, balconies and bridgework. Galvanized iron enabled the creation of graceful decorative features. The metalwork could last for generations, remaining strong and sophisticated. Designed by John Day, Guelph’s Petrie Building is one of only three remaining architectural treasures in Canada featuring a stamped façade of galvanized full sheet metal.

Businessman Alexander Bain Petrie commissioned local architect John Day to plan a four-storey stone and wood commercial building in Second Empire style, suitable for a prosperous and influential pharmacist. (Petrie was also city councillor and bank president.) Day’s plans included a ground-floor drug store with the druggist’s office on the second floor. “The third floor housed the ‘inner sanctum’ of the International Order of Odd Fellows,” stated Petrie Building in Restore the Petrie, “and was only accessible from a grand hall in the adjoining Petrie-Kelly Building.”

Day’s specialized design featured “an elaborate cast iron façade surmounted by mortar and pestle, symbols of the druggist’s trade, and fabricated entirely in galvanized metal,” described Robert Hill in Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada.

Contracting Bakewell & Mullins to create the extraordinary cladding, Day was able to personalize the building to fit the pharmacist’s needs, the Salem, Ohio manufacturer opened in 1872 to produce sheet metal statuary and cornicework, named Kittridge, Clark & Company. Changing owners and titles over the decade, the operation became Bakewell & Mullins in 1882.

A stamped galvanized iron façade “was a popular building technology of the late 1800s,” said Ontario’s Historic Places in “The Petrie Building,” and “was used as a substitute for wood, stone, or cast iron.” The Bakewell & Mullins fabrication for the Guelph structure was “stylishly ornamented and elaborately embellished,” completed by iron-work specialists.

Clients of the booming mail-order firm customized orders by selecting pieces from a catalogue. The pieces were shipped from the American factory by freight or express, according to client’s wishes. The adornments were “then attached to the building by local metalworkers,” said Petrie Building. The Guelph building’s ornamentation was “made from galvanized zinc,” and galvanized sheet steel formed the majority of the facing.

Bakewell & Mullins designed several iron-work pieces for customers desiring commercial druggist’s signage. The catalogue offered mortars and pestles in sizes from 8 inches (20 cm) to 30 inches high (76 cm). A 24-inch (60 cm) set in parts cost $7.50; a completed plain ornament was $10; and a gilded mortar and pestle came in at $21.50. (Over $723 in today’s US dollars.)

“We have in our employ some of the best Designers and Modelers in the county, and they, together with our large corps of skilled workmen, enable us to guarantee artistic treatment and perfect workmanship,” noted Bakewell & Mullins 1887 catalogue. Four years after completing the Petrie Building contract, a fire devoured the Bakewell & Mullins factory in early March 1886.

The manufacturer wasted no time in rebuilding. The owners doubled the capacity of the Stamping Department as well as enlarged the Spinning Department. (The Spinning Department used high-speed rotation to form a disc or tube of metal into a cylinder-shape.)

Over many decades, tenants and owners changed, and the Petrie Building fell into disheartening disrepair. The finial and ornamental druggist’s pestle fell off, “and the entire lower section was removed and destroyed by a former owner,” said Petrie Building.

The Petrie Building was “as a Building of Historical and Architectural Interest” by the City of Guelph on May 22, 1990. The heritage recognition was earned for architectural elements such as the “bold cornice with a broken pediment framing a large mortar and pestle,” and many “elaborate exterior details,” according to Ontario’s Historical Places.

Tyrcathlen Partners purchased the unique Petrie Building in March 2015, rescuing the landmark from a dire fate. Through government grants, crowdfunding, and fundraising campaigns, the Petrie Building has been restored to resemble its past glory. Founded in 2010, Tyrcathlen Partners specializes in restoration of heritage properties in Guelph. The historical building is once again thriving, alive with tenants, clients, and shoppers.

The life of the productive John Day was less favorable. Born in Guelph in 1849 to a builder, “he may have been trained under his father,” said Hill, as well as working for a time in Cleveland, Ohio. Day established his architectural practice in about 1874 and received commission to design commercial buildings, homes, schools, hotels, and more.

Day was working on reconstruction of the Commercial Hotel in 1888 when he “sustained a serious spinal injury as the result of a fall,” mentioned Hill. “This event appears to have curtailed his activity as an architect.” In November 1896, John Day “was found dead from self-inflicted gun wounds.” It was a sad ending to his once-flourishing career. The Petrie Building remains as Day’s legacy of fine architecture in the 19th century.

© 2025 Susanna McLeod. She is a writer specializing in Canadian history.