Susanna McLeod

Special to Canadian Design and Construction Report

Ahead of his time, Orson Fowler dove into architecture, before programs were available. Why build four-sided rectangular homes, he questioned in the 1840s, when you could build an eight-sided residence? An octagonal home was spherical, and “allowed for economy of space, admitted increased sunlight, eliminated square corners and facilitated communication between rooms,” described Madeleine Stern in the reprinting of Fowler’s 1853 book, The Octagon House: A Home For All (1973) A trained phrenologist, the amateur architect inspired a building boom of affordable octagonal homes, including many in Ontario.

Orson Squire Fowler was born in Cohocton, New York on October 11, 1809 to church deacon Horace Fowler and his wife Martha. The boy enjoyed higher education, and in his late teens, Fowler was immersed in studies to become a church minister. By chance, a classmate was interested in phrenology—determining a person’s character by feeling the bumps and dips in the skull. Fowler was captivated. The student became an expert in the then-fashionable precursor to modern psychology. (Phrenology is now considered a pseudoscience.)

As editor of American Phrenological Journal, Fowler published articles and books on phrenology with a sincere belief that the philosophy was helpful to clients. He ventured into marriage counselling and sex education, as well as advising clients on occupations. Fowler supported women’s rights and equality, and understood the relationship between brain function and good health. “He opposed the use of tobacco, tea, coffee, and alcohol, feeling they all weakened moral and intellectual powers,” said EBSCO Research. Confident in his own intellectual capabilities, by the 1940s, Fowler changed his career path.

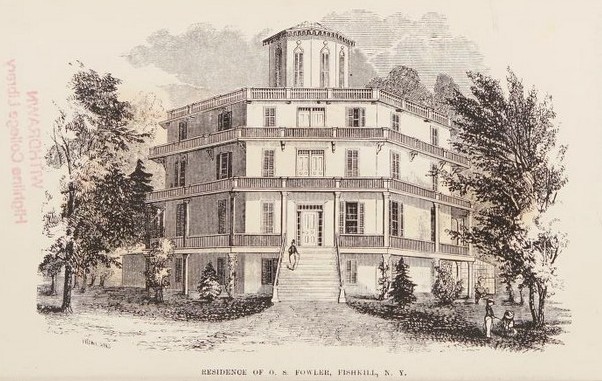

Architecture intrigued the young publisher. “Without any previous experience, he planned, designed, and built a sixty-room octagonal house in Dutchess County, New York,” said EBSCO Research. “It was an extraordinary building, constructed of gravel, a substance rarely used as a building material.” (Fowler’s ‘gravel’ was concrete.)

At ground level, Fowler’s lowest floor was the basement. It should be the “thoroughfare” of the home, not “through your main storey, for this will bring in the most dirt where it is most troublesome, namely, near your nicest rooms.”

The amateur architect’s own massive home featured “four tiers of encircling verandas; a rooftop belvedere or lookout,” and concrete walls that were “rusticated or scored to imitate cut stone,” noted John Blumenson in Ontario Architecture (Fitzhenry & Whiteside 1990). Fowler installed innovative systems, such as “fresh air ventilators and speaking tubes to all levels,” plus hot and cold running water, a bathroom, and gas-powered heating and lighting. He adapted his eight-sided design for school houses, churches, and barns. (Inside bathrooms were not standard in Ontario until well into the 1900s.)

Every person needs a home, believed Fowler. The structure does not need to be fancy or complicated, “it matters less what a house costs,” Fowler wrote, “than how GOOD it is.” Architectural training was not necessary, he deemed, and that the mature, intelligent person had the ability. “Those of well-balanced minds and sound practical sense, will plan and execute a comfortable, good-looking, well-arranged residence, which they will finish off in a style corresponding with their own order of taste.”

Enchanted with nature’s smooth elements such as apples, eyes, and planets, Fowler considered angles unattractive. He preferred the dome roof to the cottage roof, “full of sharp peaks, sticking out in various directions, and say if the undulating regularity of the former does not strike the eye far more agreeably than the sharp projections of the latter.”

Insulation was but a notion in the 1800s, therefore Fowler’s calculations allowed for thick walls from 20 cm to 40 cm. Using hemlock for his first home, he stated that other types would be useful since there was less strain on materials with his design, and that a coat of mortar would prevent rot. Calculating costs in 1848, the amateur architect stated, “Believe me, when I say that lumber, pins, labor, and nails, to put up the outside and inside walls—both of which must go up together—of a house thirty-two feet square, or of this dimension, whatever be its shape, will not cost you $80 dollars!”

Holding lecture tours throughout North America, Orson Fowler promoted his octagonal home as an affordable, healthy architecture. Fowler died on August 8, 1887. His phrenologist reputation was tarnished by his overstepping, but his renown for octagonal architecture was intact.

Registering the first guide to his architectural achievement in 1848, Fowler’s book was reprinted frequently to meet surging demand. A Home For All was sold across North America, and by 1857, more than one thousand octagon-style homes were built in the United States and Canada; more homes were constructed until the 1890s.

Unique Fowler-designed homes are dotted across Ontario, at Hawkesbury, Brampton, Maple, Cobden, and other locations, with a range of exteriors from concrete and stucco to red brick.

© 2025 Susanna McLeod. Living in Kingston, Ontario, she is a writer specializing in Canadian history.

Sources:

Blumenson, John, Ontario Architecture: A Guide to Styles and Building Terms 1784 to the present, Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1990: p. 72-76.

Fowler, O.S., A Home for All or a New, Cheap, Convenient and Superior Mode of Building, Fowlers and Wells Publishers, 1850: p. 51. (Google Books)

Fowler, Orson S. The Octagon House: A Home for All, Dover Publications, Inc., 1853/republished Dover Publications, Inc., New York 1973. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/octagonhousehome0000fowl/page/n3/mode/2up

“Research Starters; Orson Squire Fowler,” EBSCO Research. Retrieved from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/orson-squire-fowler